As a coach, you may have suggested icing a sore ankle or taking a hot bath after a grueling practice to alleviate aches and pains. But some of the age-old recommendations around ice and heat have been debunked. Ice and heat still have a place in an athlete’s recovery, though, and can be incredibly useful tools when applied appropriately.

As a coach, you may have suggested icing a sore ankle or taking a hot bath after a grueling practice to alleviate aches and pains. But some of the age-old recommendations around ice and heat have been debunked. Ice and heat still have a place in an athlete’s recovery, though, and can be incredibly useful tools when applied appropriately.

Dr. Michele LaBotz, TrueSport Expert and sports medicine physician, will explain some of the best practices around using heat and ice for recovery, but notes that both are rapidly evolving fields of research. She expects to see a lot more research on how heat, in particular, works for athletes. In the meantime, here’s what we know.

Recovery is a nuanced process

Unfortunately, the entire topic of recovery—especially in terms of temperature—is very nuanced. What works well for one athlete may not work for another, and best practices are rarely clear-cut. For instance, using ice to help with inflammation right after an ankle sprain is going to be helpful, but using too much of it a few days later may actually slow the healing process, LaBotz says. So, try to avoid giving athletes any “one-size-fits-all” recommendations.

For acute injury, use ice

“If you sprain an ankle during a game and you’re on the sidelines with an ankle that is swelling up, that’s an inflammatory process that is out of control,” says LaBotz. “Putting ice and some compression on the ankle to keep inflammation under control in that acute setting is a reasonable thing to do, and your best first step.”

“If you sprain an ankle during a game and you’re on the sidelines with an ankle that is swelling up, that’s an inflammatory process that is out of control,” says LaBotz. “Putting ice and some compression on the ankle to keep inflammation under control in that acute setting is a reasonable thing to do, and your best first step.”

But stop icing it eventually

While ice is a good idea in the first stages of an injury, it shouldn’t be something you use non-stop. “One of the concerns about the use of ice is that it slows down blood flow. That means that it slows down the inflammation, and it slows down all the enzyme reactions that are part of the inflammatory process,” LaBotz explains. “While inflammation sounds like a negative, it is actually necessary and part of the healing process that needs to occur at some point.”

“There have been some studies showing that athletes don’t replenish glycogen as quickly if they have a muscle that’s been iced down,” she says. “Old recommendations were to continue to ice a spot a few times a day until the soreness went away. But because we want injuries to begin to heal, we want blood flow to come in and we want cells to have access to glycogen and glucose so they can do the healing work. With that in mind, you need to strike a balance between icing to alleviate pain and inflammation and allowing inflammation to do its job.”

Heat helps… eventually

Heat application won’t help much on the sidelines of a game, but post-practice heat application is a good idea. “You would use heat in the short term to help with pain or muscle soreness,” says LaBotz. “But some of the newer data on the role of heat in recovery and repair suggests that over the longer term, using heat can stimulate the growth of capillaries and turn on the enzymes to start the repair and muscle building process. This effect may ultimately help support optimal performance and recovery, which reinforces the consistent use of heat, but these changes take time and aren’t expected to result in any immediate impact for the athlete,” she explains.

Be smart about cold application

There’s a fine line between too cold and not cold enough. Occasionally, there are issues with frostbite from chemical packs, LaBotz says. But more frequently, athletes have such a thick towel between their body and the icepack that the ice can’t actually cool the muscles. “You want the cold penetrating into the injury,” LaBotz says. “You get the best conveyance of cold using something like a dampened thin kitchen towel over the ice pack.” And don’t leave it on past the point of discomfort. If you’re noticing more discomfort because of the ice, or if the area starts going numb or tingling, take the ice pack off.

There’s a fine line between too cold and not cold enough. Occasionally, there are issues with frostbite from chemical packs, LaBotz says. But more frequently, athletes have such a thick towel between their body and the icepack that the ice can’t actually cool the muscles. “You want the cold penetrating into the injury,” LaBotz says. “You get the best conveyance of cold using something like a dampened thin kitchen towel over the ice pack.” And don’t leave it on past the point of discomfort. If you’re noticing more discomfort because of the ice, or if the area starts going numb or tingling, take the ice pack off.

Skip the ice vests

You may be tempted to recommend ice vests or other icy cooling solutions to your athletes on hot days. But LaBotz recommends that instead of ice vests, your athletes focus on minimizing time in the direct sun and sipping icy water or sports drink before their practice or game. “Athletes need to be aware of the environmental risk, and with ice vests on, they may not realize how hot it is until they’re playing,” explains LaBotz.

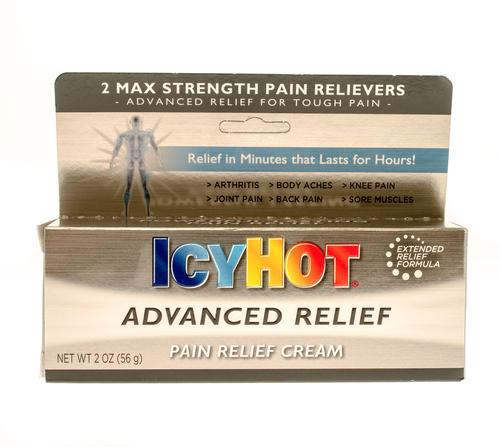

Hot and cold gels and lotions aren’t the same as ice and heat

You might be tempted to grab a balm or gel that offers “heating and cooling” action. But while these topically applied rubs might feel icy or hot and may relieve discomfort, they aren’t doing anything for the healing process. “These balms just give the sensation of cooling,” LaBotz says. “They don’t change the temperature of the muscles. When we’re discussing the effects of heat and cold, we’re talking about enough heat or enough cold to change the temperature of the muscles beneath. The cooling from a gel is mental. It distracts the nerves from the pain, which can be helpful. But it’s not going to give you the same effects as actually heating or cooling the area.”

You might be tempted to grab a balm or gel that offers “heating and cooling” action. But while these topically applied rubs might feel icy or hot and may relieve discomfort, they aren’t doing anything for the healing process. “These balms just give the sensation of cooling,” LaBotz says. “They don’t change the temperature of the muscles. When we’re discussing the effects of heat and cold, we’re talking about enough heat or enough cold to change the temperature of the muscles beneath. The cooling from a gel is mental. It distracts the nerves from the pain, which can be helpful. But it’s not going to give you the same effects as actually heating or cooling the area.”

______________________

Takeaway

While using heat and ice for injuries is a nuanced topic with rapidly emerging research, there are some best practices to keep in mind when helping your team recover safely and effectively.