A healthy relationship with food is one of the many things parents are supposed to help children develop. We want them to choose fresh before packaged, fruit before fruit-flavored, and vegetables before they get fried. But beyond the foods themselves, the times and reasons we eat also play major roles in establishing our relationship with food. Youth sport practices, games, and tournaments are packed with snacks and sports drinks, which leads the question: Are we over-snacking our young athletes?

A healthy relationship with food is one of the many things parents are supposed to help children develop. We want them to choose fresh before packaged, fruit before fruit-flavored, and vegetables before they get fried. But beyond the foods themselves, the times and reasons we eat also play major roles in establishing our relationship with food. Youth sport practices, games, and tournaments are packed with snacks and sports drinks, which leads the question: Are we over-snacking our young athletes?

Why there’s so much food in youth sports

Every parent has stories about the time(s) their kid went from fine to full meltdown in the span of five minutes, only to rebound equally quickly after getting some food down the hatch. That’s why we all have secret stashes of crackers, granola bars, or fruit gummies in backpacks, handbags, and car consoles. But according to research from Toben Nelson at the University of Minnesota, despite expending more energy than non-sport participants, kids who participate in youth sports often end up consuming more calories than they expend – and a lot of it is junk food. Here are some of the contributing factors:

- Time constraints – Shuttling kids from activity to activity means more eating in the car, more stops at convenience stores and drive-thrus, and more packaged foods.

- Overlap – It’s not that youth sport athletes get one extra snack compared to non-sport peers, but rather that they get multiple extra snacks: before the game, halftime, after the game, or at the next game later in the afternoon.

- Sponsorships – Youth sports leagues and school sports programs can always use more funding, and companies that make sugary beverages and snacks are right there to help.

- Marketing – Sports drink companies pay millions of dollars to ensure kids make the connection between the bottle in a pro athlete’s hand and the very same bottle they can have, too!

But, they burn so much energy!

Not really. A study by Wickel and Eisenmann used accelerometers to examine the contributions of youth sports, physical education class, and recess to the activity level of 119 boys between the ages of six and 12 years old. Out of 110 minutes of ‘moderate to vigorous physical activity,’ 23% was from youth sports, and 27% was from PE and recess (11 and 16%, individually). Perhaps more surprising was the finding that more than half the time spent in youth sports was sedentary or light activity.

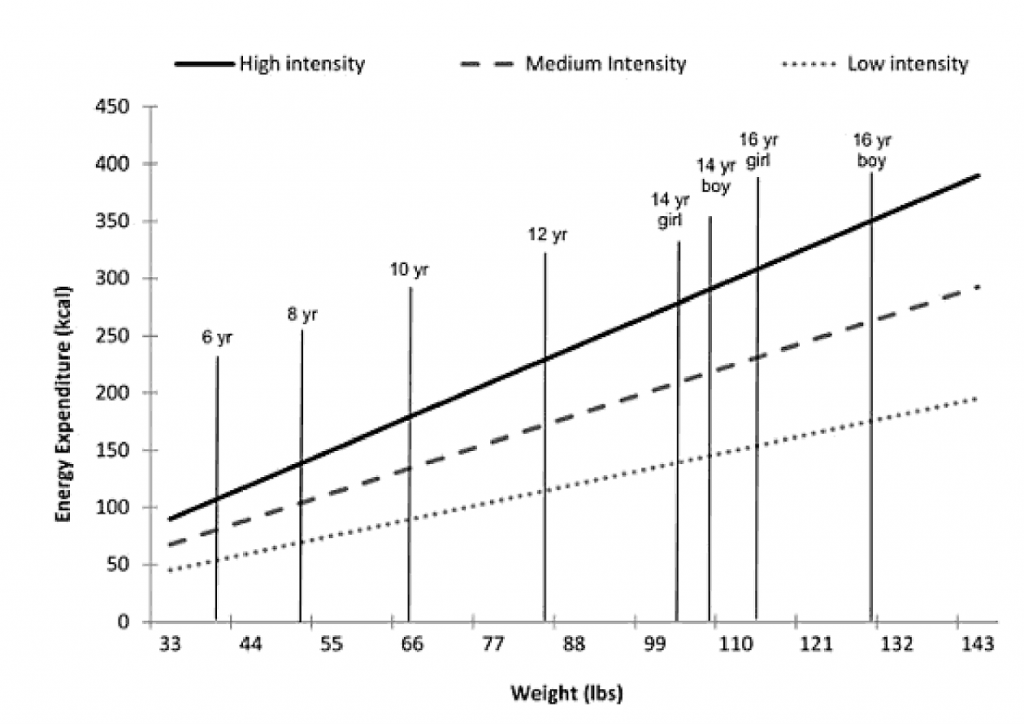

Toben Nelson created a graph to illustrate the approximate caloric expenditures of youth athletes ages six to 16 years old during 60 minutes of light, moderate, and intense physical activity. An 8-year-old boy at the median weight for his age would burn approximately 150 Calories in an hour of continuous intense activity. Considering the amount of low-intensity time during games, the actual expenditure is likely even lower.

Over-Snacking Leads to Poor Eating Behaviors

Basing eating behaviors on habit instead of hunger is a contributing factor for obesity at any age. In an interview for Parents.com, childhood feeding specialist Dr. Katja Rowell, M.D., commented, “When kids are allowed to eat all day, it robs them of the chance to ever develop an appetite.” In other words, they feel hungry more frequently because they are unaccustomed to being unfed for prolonged periods of the day. If you’re used to eating every two hours, four hours without food will seem interminable.

Snacks as a pre-requisite for activity, or snacks as a reward for activity, can also establish poor eating behaviors. Encouraging kids to fuel up before practice or a game, replenish energy during a game, and then finish every activity with a snack or sweet treat as a reward, can condition them to make an unhealthy association between activity and food. In teenagers and adults this can manifest as ‘caloric overcompensation,’ the tendency to overeat based on an over-estimation of calories expended and calories necessary to support their activity level.

How to Get Sports Snacking Under Control

There are some positive aspects to establishing routines around eating and drinking during sports. It is important for kids to stay hydrated, especially during hot-weather activities, and bringing athletes together at regular and expected times to drink helps establish the habit of drinking during exercise. But most times it should be water. Similarly, getting the team together at halftime and after the game is important for building strong relationships and learning how to celebrate when you win and support each other when you lose. But to cut down on the excess sugar and calories, consider the following:

- Emphasize water over calories. Provide fruit with high water content, like orange slices and watermelon, at halftime and after the game.

- The American College of Sports Medicine recommends carbohydrate-rich sports drinks only for activities lasting longer than 60 minutes.

- Speak up! No one wants to rock the boat, but you are probably not the only parent who would support fewer snacks at games.

- Reserve sweet treats for an earned reward. Establish a reward the team can work toward based on effort, not victories. Over the course of a season or portion of a season, the team could be rewarded for hustle, listening during practice, or improving an aspect of performance they can control (free throw scoring percentage, for instance).

References:

Messner, Michael A., et al. “Sport and the Childhood Obesity Epidemic.” Child’s Play: Sport in Kids’ Worlds, Rutgers University Press, 2016.

Nelson, Toben F., et al. “Do Youth Sports Prevent Pediatric Obesity? A Systematic Review and Commentary.” Current Sports Medicine Reports, vol. 10, no. 6, 2011, pp. 360–370.

Kuzemchak, R.D. Sally. “The Snack Epidemic.” Parents, Parents, 5 Jan. 2016, www.parents.com/recipes/nutrition/kids/the-snack-epidemic/.

Wickel, Eric E., and Joey C. Eisenmann. “Contribution of Youth Sport to Total Daily Physical Activity among 6- to 12-Yr-Old Boys.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 39, no. 9, 2007, pp. 1493–1500.